Chicago as a case study in the limitations of social media datasets

From oracles and prophecies, to fortune-tellers and magic 8 balls, it’s been a part of human nature to want to believe that if we ask the right questions of the right source, we can get all the answers. One of the twenty-first century’s incarnations of this phenomena is data fundamentalism, or the belief that, given how much data we continuously generate in our waking (and sleeping) hours, we can use it to solve all our problems, including death. (That is, as long as we gather enough of it and ask it the right questions).

But, there are hidden biases in big data and artificial intelligence rooted in how we collect this data and for what purpose. Really, the danger in this thinking is not that we can’t find significant and interesting results from analyzing these massive sets of data. It’s that the analyses of data generated from our social media-entrenched, smart device-embedded, app-reliant existences render invisible significant portions of the population.

In Chicago, for instance, who is missing from the treasure trove of Instagram data that is touted as the new frontier for research into human behavior in urban cities? By exploring the racial/ethnic profile of the city, we see that particular populations are omitted and that the potential implications for policy based on this reality is troubling.

Case in point: Chicago’s Instagram Presence

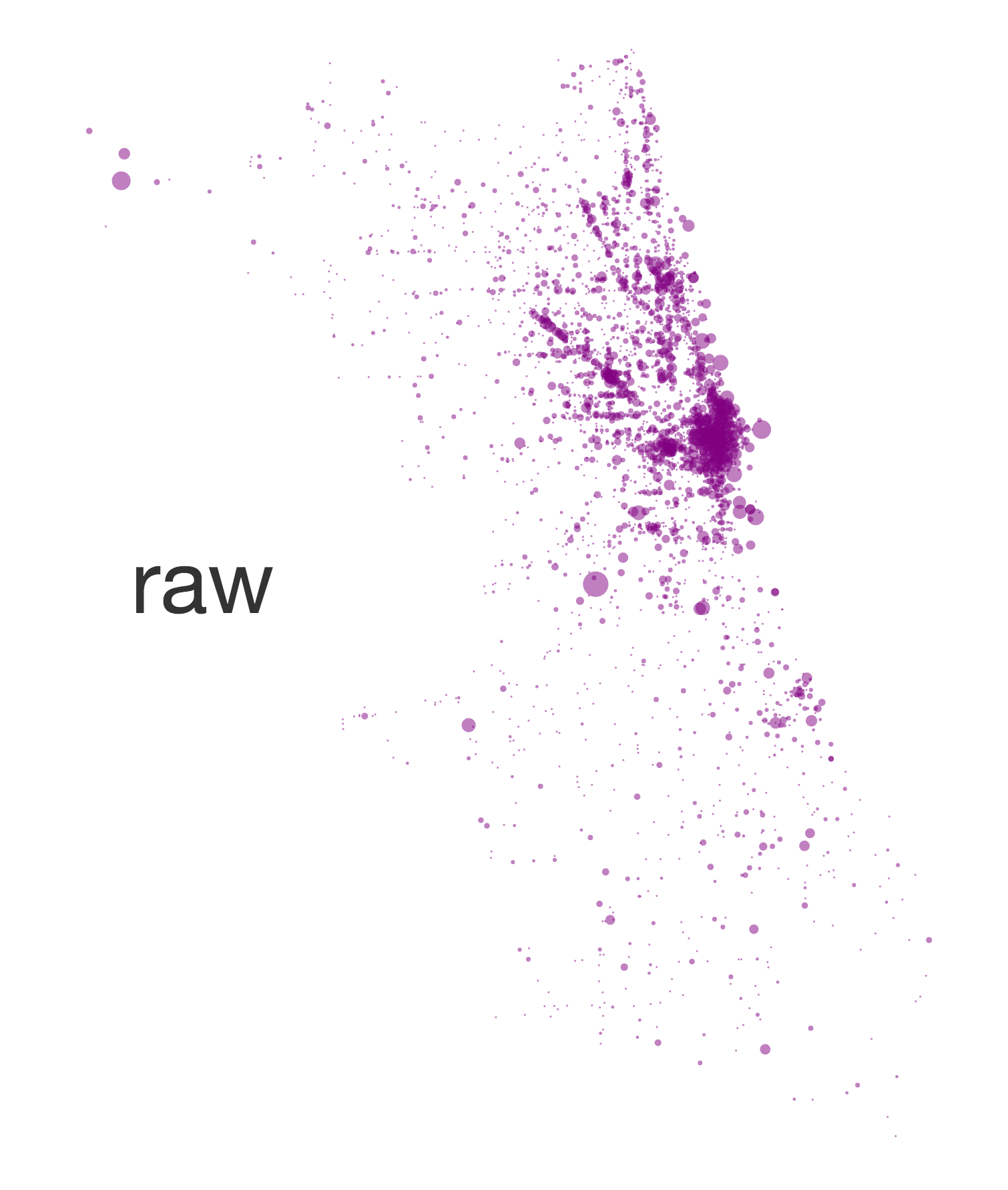

Instagram data, though generated by one of the most widely used platforms Over 300 million users who share over 70 million photos a day (in 2015) is still contingent on people having both access to smartphones and interest. Consequently, there will always be sampling bias in its analysis. Of course, who exactly is left out depends on the particular demographic profiles of a given location (and the platform in question). What follows is an exploration of 30,908 geotagged Instagrams from Chicago collected during June 2016 to see who is over- and under-represented based on 2010 census data.

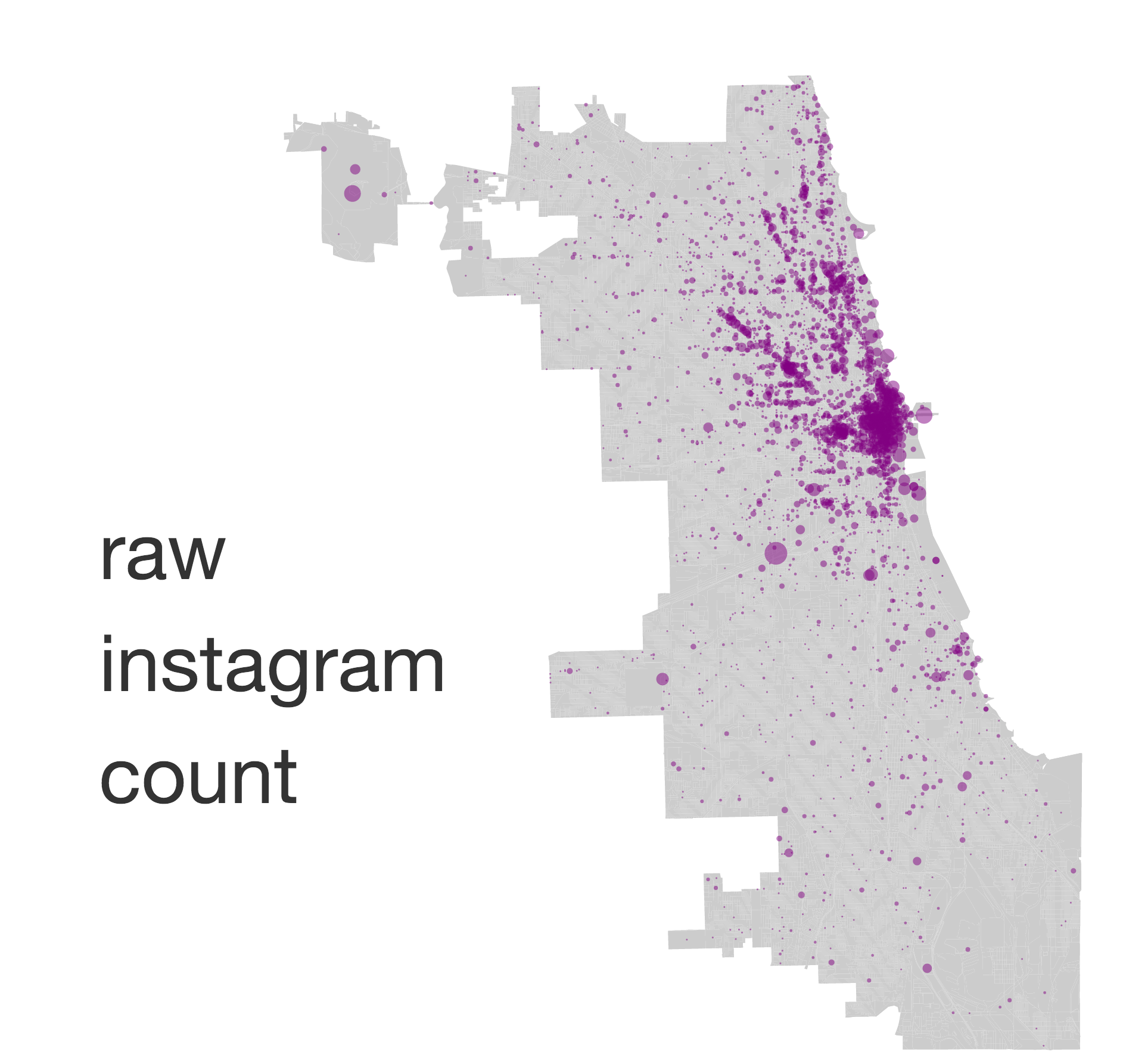

When we map geotagged Instagram activity in Chicago to city blocks as defined by the smallest geographic unit used by the census (i.e., census blocks which correspond roughly to 1 city block). Each dot represents a city block with Instagram activity and is scaled to the log of each count. We can quickly see that clusters of activity exist near the city center (i.e., the Loop) and along what appear to be city’s CTA transit lines headed north. What does it actually mean? Maybe this is just an accurate representation of where people live in the city… Let’s see!

Is Instagram just another proxy for Chicago’s Population (2010 census)?

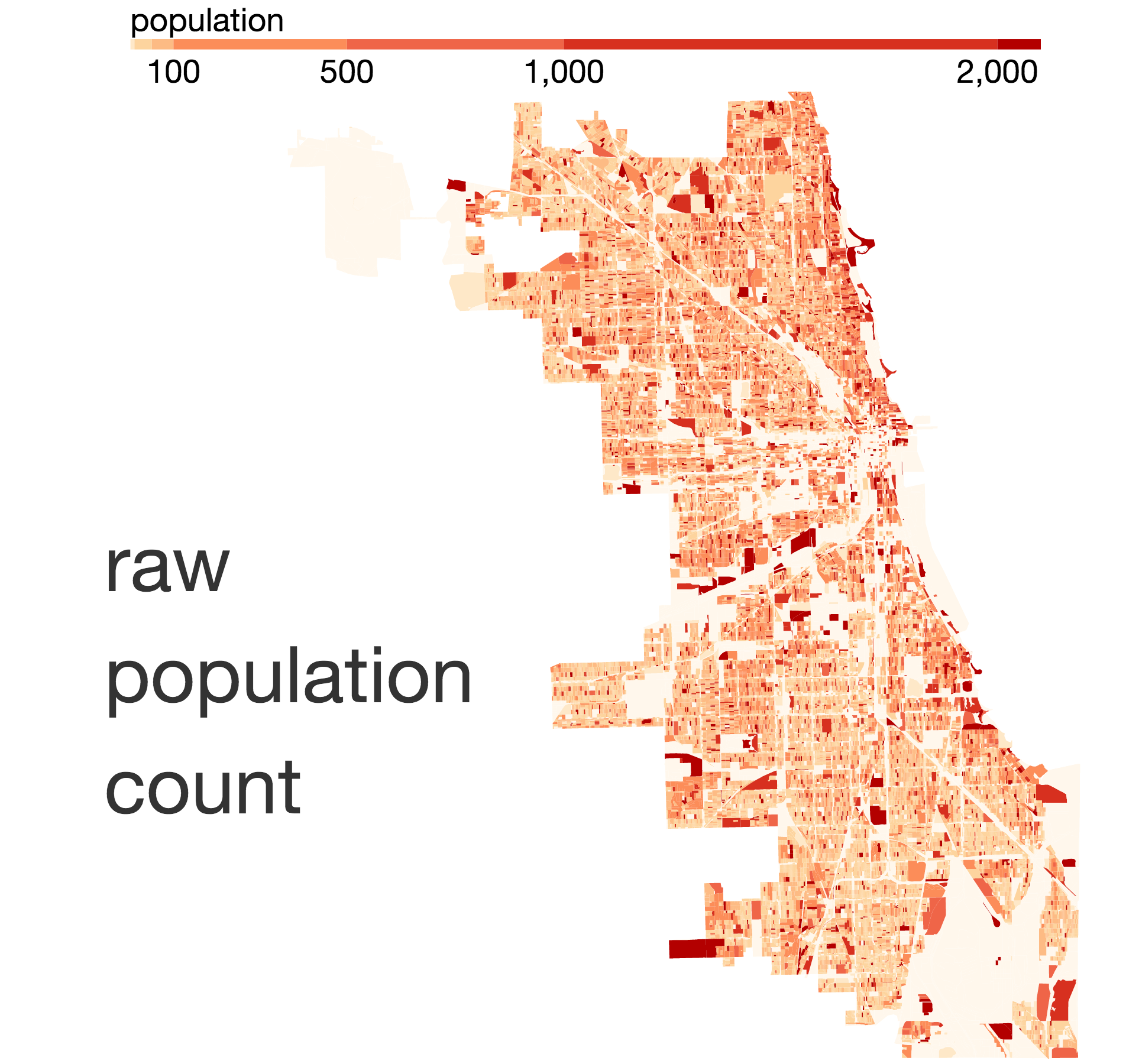

NOPE. Looking at census population counts, high concentrations of people appear to be distributed throughout the city. Something to note though is that these census blocks are NOT created equal.

NEXT STEP: What if we take into account population density? Will that account for the clustering we see in Instagram data?

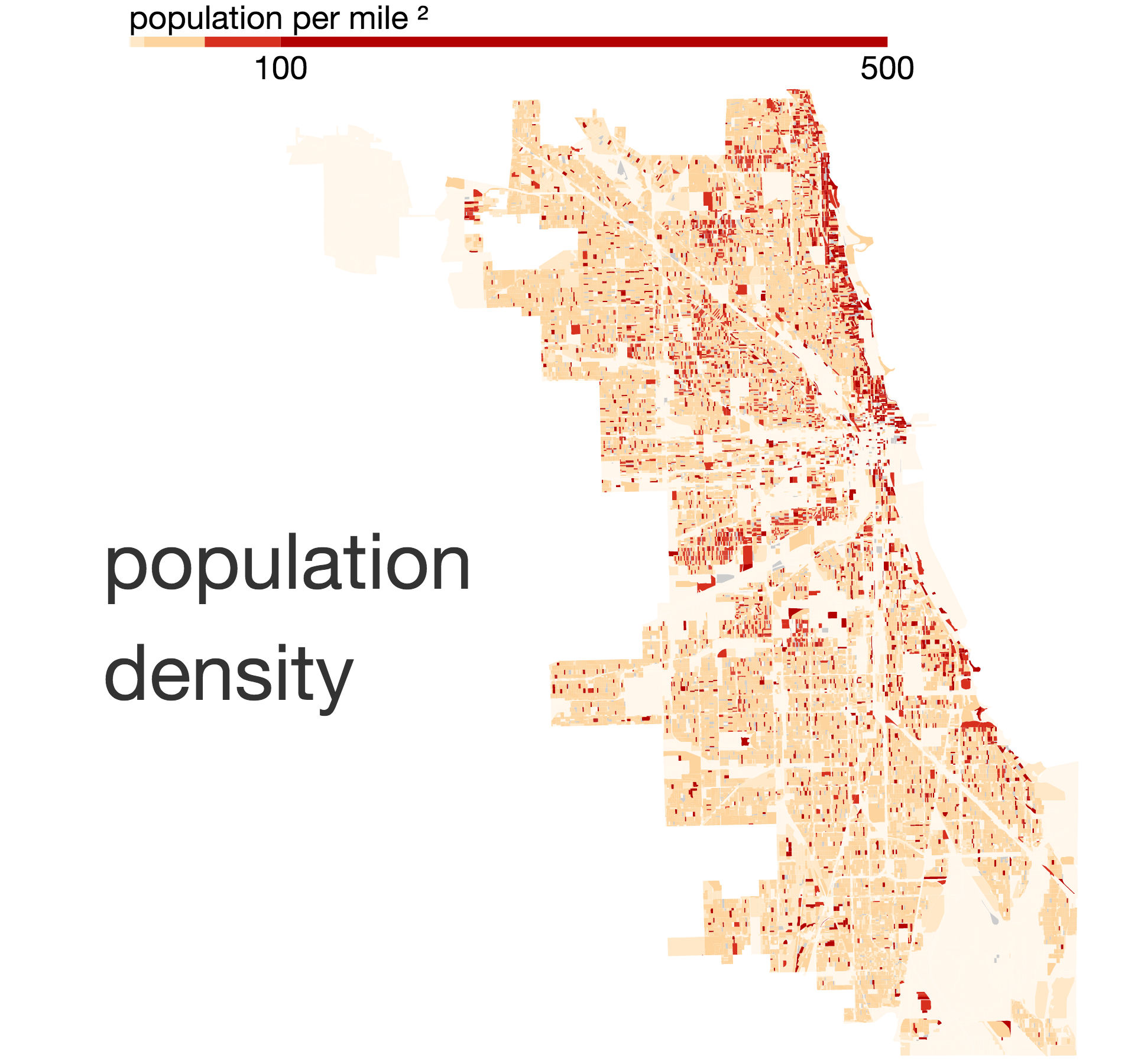

STILL NOPE. By accounting for area size, we’ve stripped away some noise from the population patterns. There are clear clusters of highly dense areas. Along the eastern border (i.e., the lake for the non-Chicagoans) there is higher density throughout but especially north of the Loop. There is also a high density patch going due west of the Loop. The rest of the north-side tends to be denser as well, but in looser contingents than lake-side. The northern pattern may mimic Instagram but that western swell sure is a surprise!

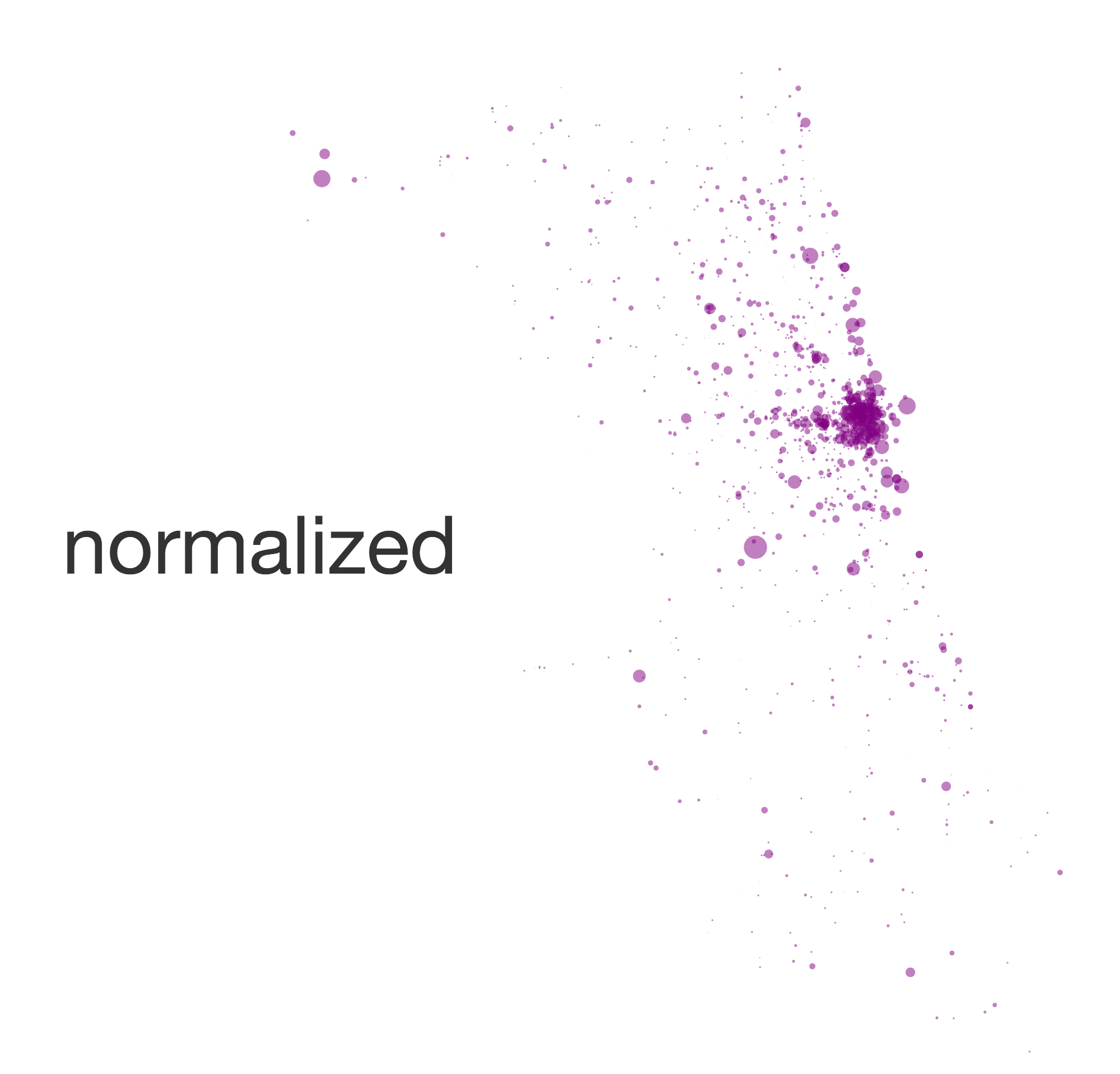

NEXT STEP: Let’s similarly factor population into how we display the city’s Instagram presence.

Instagram Activity Normalized for Population

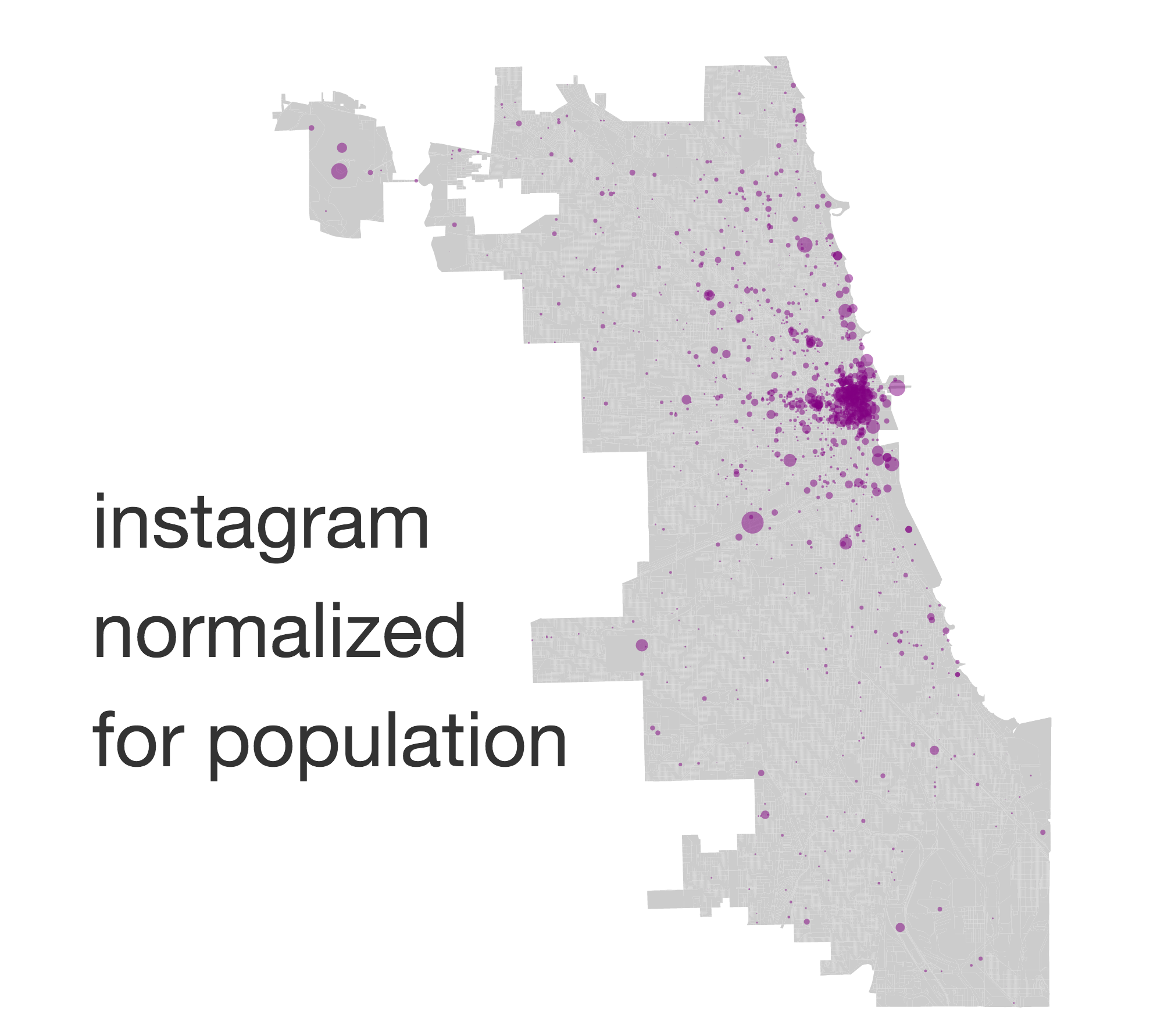

Poof! We’ve stripped out some of the noise. Now we can see that it’s not only Chicago’s population density that drives the north-side’s dominance of the city’s Instagram presence.

NEXT STEP: Let’s see what areas are over- and under- represented.

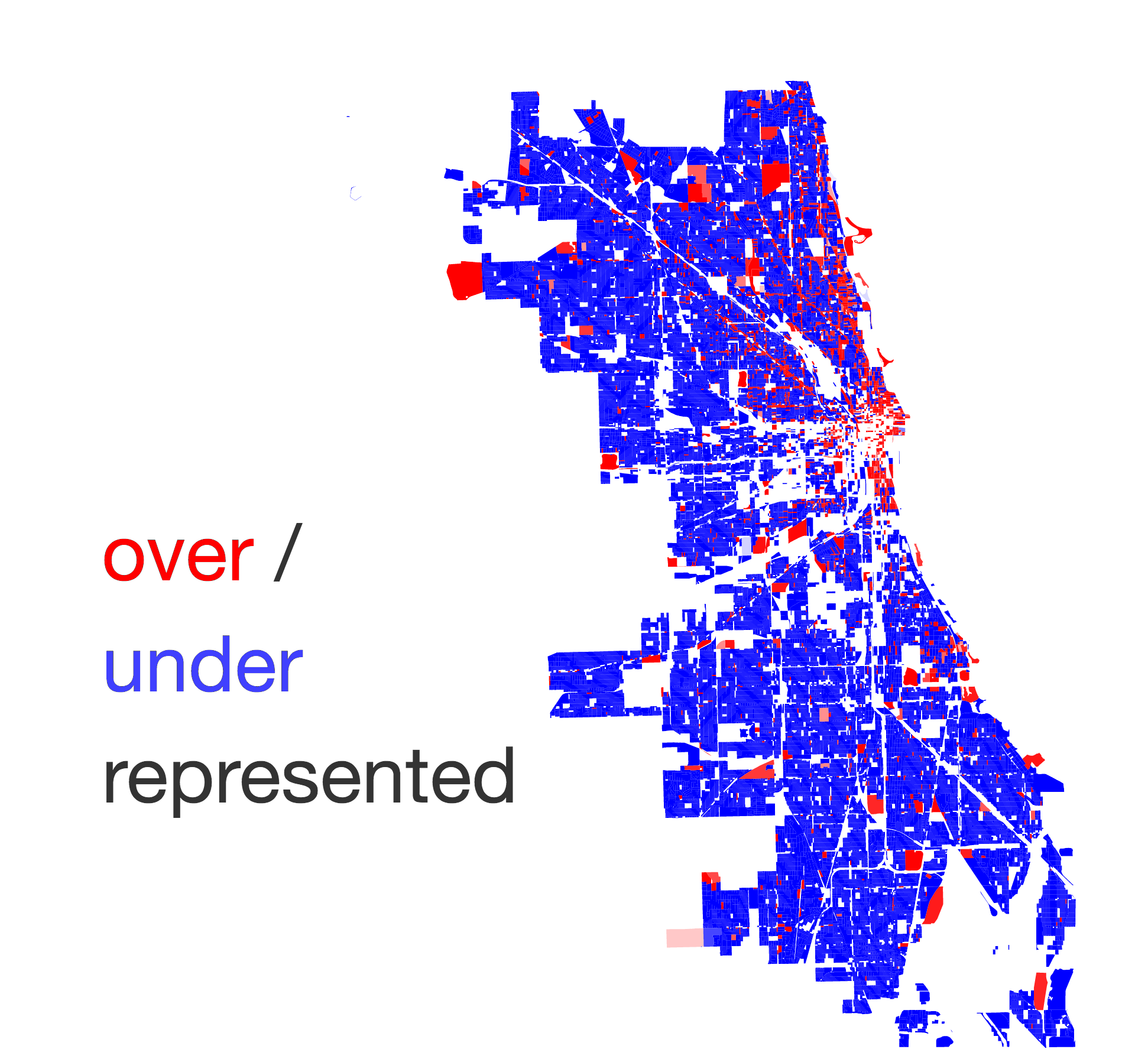

Representation Across City Blocks

All blocks in Chicago are clearly NOT created equal in terms of Instagram presence. In fact, most of the city is underrepresented. To determine over- and under-representation by city block, calculate the weight-adjustment needed to make each area’s Instagram count reflect its portion of the city’s total population. One can do this by dividing the percent of the total population in each block by its percent of total Instagram activity. All weights below 1 (with 1 being representative) reflect over-representation in the sample and weights higher than 1 reflect under-representedness. The weight shows how many more times a given area’s activity needs to be counted to match its portion of the population.

Note: Areas with no population are displayed as representative; this has the effect of counting less places as over-represented (i.e., parks, museums, airports) but hopefully helps somewhat mitigate the inclusion of tourist activity.

The overrepresented blocks are clustered near the city center (i.e., the Loop, an area of low population density but a high number of daytime workers and tourists) and north-side blocks near the lake and the transit lines.

NEXT STEP: Let’s look at Chicago’s racial/ethnic demographic by mapping census data.

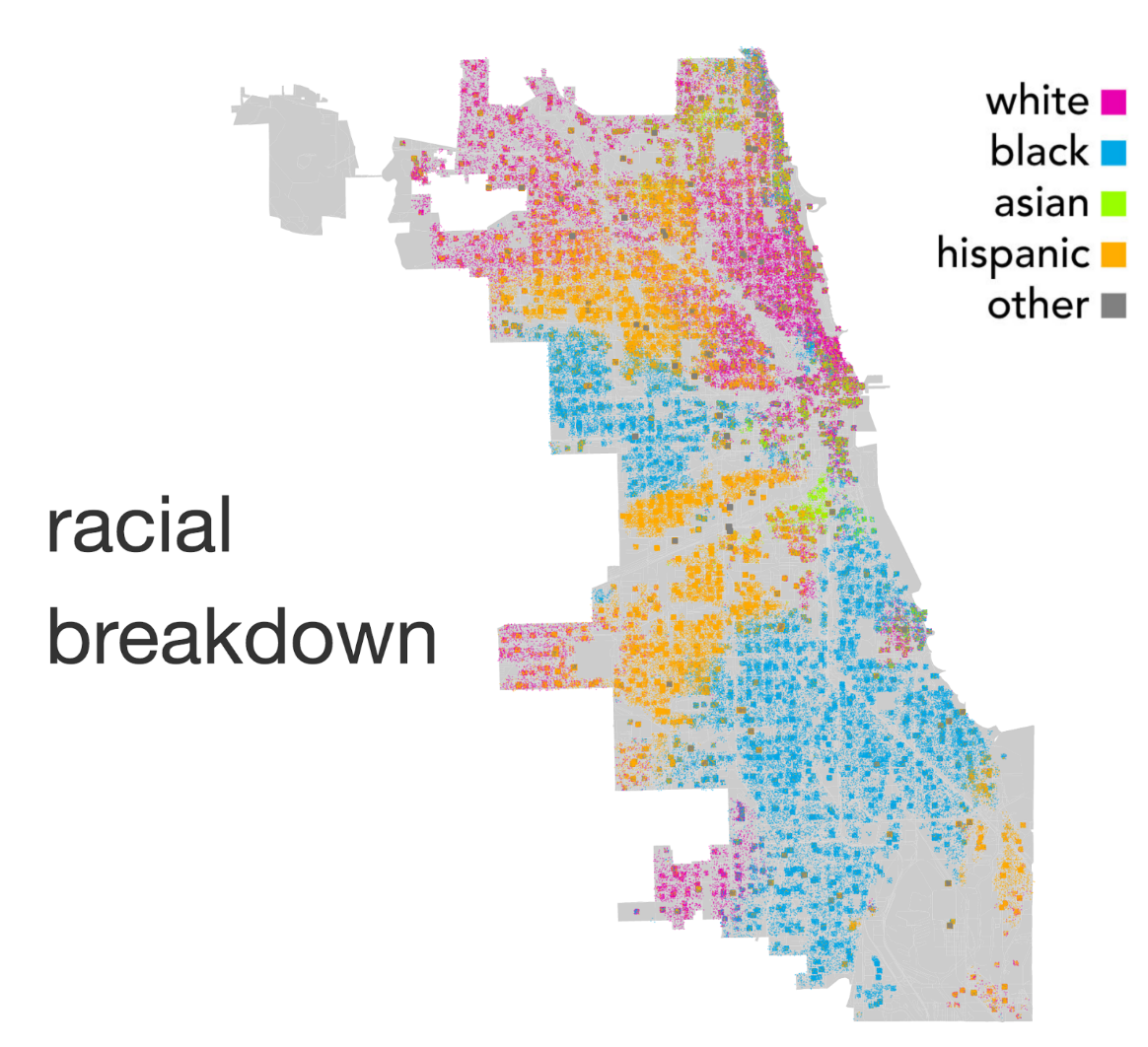

Racial Demographics Mapped to City Blocks

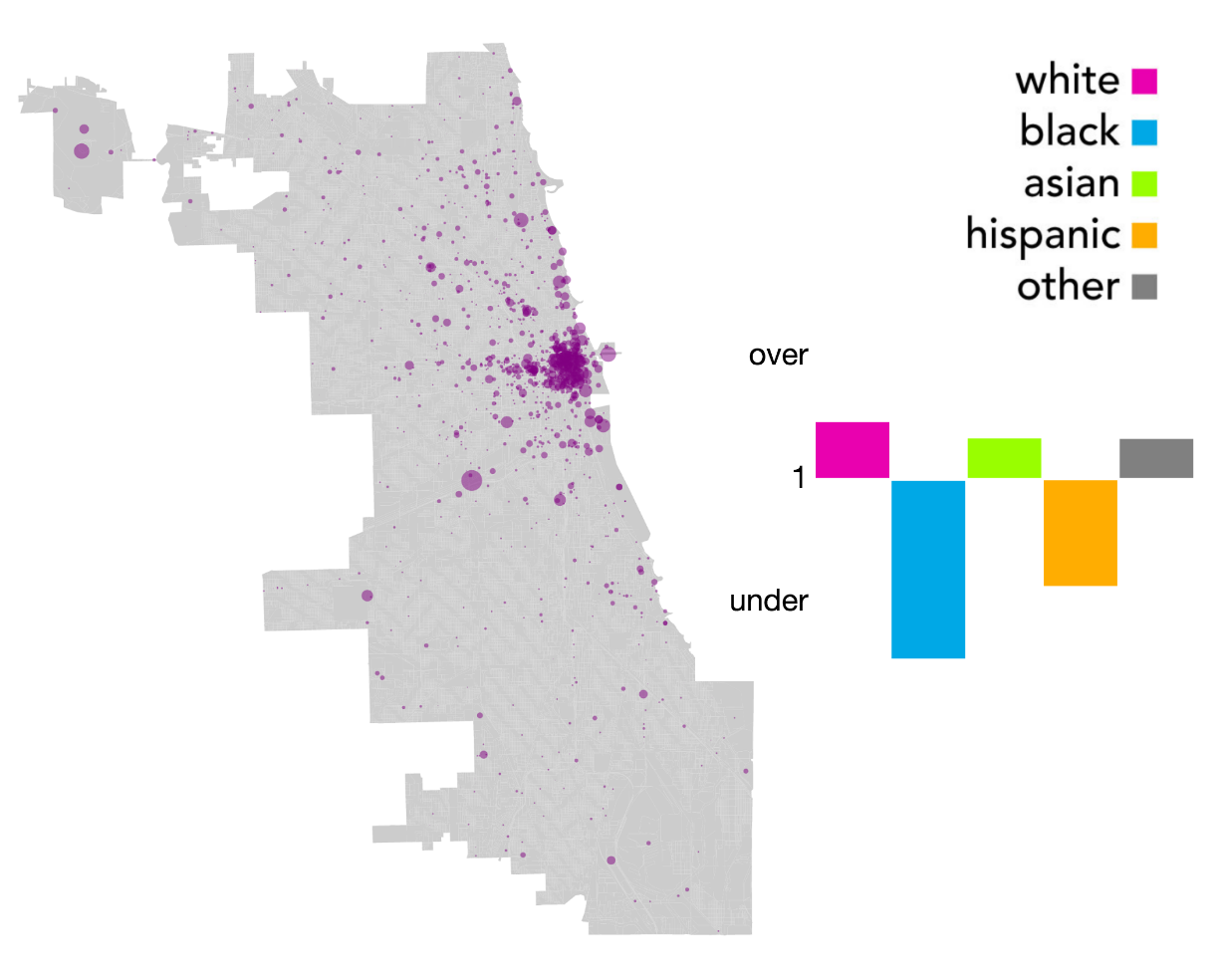

When we map racial demographics to city blocks, mapping involved combining racial/ethnic self-identification data from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 (SF1) P5 Table (Hispanic Or Latino Origin By Race) with geography (i.e., census block shapefiles). The census distributes this data for census blocks by state and includes many categories & overlapping subcategories. Extracting population counts for 5 mutually-exclusive identifications (that sum to total population), IL data was mapped to city shapefiles to filter for Chicago. The remaining data was then plotted; each dot represents 25 people with the same racial/ethnic self-identification. This viz inspired by Radical Cartography. We can see at even a cursory glance that race is far from equally distributed in Chicago. This revelation, though not groundbreaking, has troubling implications when considering the earlier map of Instagram data-which now appears to be heavily biased towards white populations in the north of the city.

NEXT STEP: Let’s see how race is represented in Chicago’s Instagram to see who exactly is missing.

Racial Representation in Chicago’s Instagram

Based on this picture, some populations are clearly underrepresented when their Instagram activity levels are compared to their portion of the Chicago’s population. Similar to determining over- and under-representation by city block, each race/ethnic group’s representation is calculated by dividing the group’s portion of the total population (e.g., % of total pop.) by the group’s portion of Instagram activity (e.g., % of Instagram). To determine the latter statistic, each group is assigned a portion of each city block’s activity as proportional to the group’s portion of the population for that block. Activity in blocks without populations is omitted. Caveat: this method is only a proxy to the actual demographics of users and runs the risk of over-representing under-represented groups and relies on numbers that may no longer be completely accurate for each city block as demographics shift within the city. It would require black populations to more than double (2.44 times) and hispanic populations to almost double (1.86 times) their current Instagram activity in order to match their population numbers (30% and 29% respectively), while white and asian populations are over-represented as compared to their numbers (34% and 5%).

SO SOUTHSIDE JUST DOESN’T USE INSTAGRAM?

Maybe, but maybe not. We can’t tell. Truthfully, it’s hard to make any claims at this stage because we only see where Instagram activity is concentrated, not why it’s concentrated there. Something that adds complication to the interpretability of this data and these observations is that it all relies on what is publicly available. It is quite possible that there are several contributing factors to the final picture that gets painted by the results. For instance, tourists might be overwhelming the dataset and their movements bias the picture away from areas that are predominantly black or hispanic. Conversely, populations which have been historically victims of police harassment and abuses of authority may have a greater tendency to keep their privacy settings set to prevent public sharing of their data. To add to haze, another complication is that all populations may tend to take pictures in certain areas (e.g., trendy/tourist spots) and “the who” in the equation is further occluded by “the where”. At this stage, more research is needed into why the north dominates Chicago’s Instagram. It’s important to note, however, that any study based on this data faces these exact same limitations. If they are not made explicit, it is easy to reach wrong conclusions by forgetting about this bias.

But does this even matter?

YES, IT MATTERS… OR AT LEAST IT CAN

It really depends on the questions we ask and the ultimate users / interpreters of our output. Exploring social media is far from a fruitless endeavour as it can provide researchers with rapid access to information mapped to space and time. There are opportunities for more fine-grained and up-to-date glimpses into dynamic network analyses and to provide rapid emergency relief efforts. But, as these contributions increasingly influence public policy (e.g. law enforcement allocation and reducing demand on public services) we have to remember their inherent limitations before we start acting on the latest Instagram insights. Imagine, for instance, if intervention programs were put in place to combat youth drinking based around the behavior patterns of only a subset of Chicagoans. Would the best practices based on the network dynamics of white teens lake-side be generalizable to all youth? Or would the particular characteristics of different subcultures and status hierarchies limit its reach?

SIDE NOTE: This is not to say that every analysis is fraught with problems. For instance the following are probably not limited by the geographical bias I just highlighted:cats of instagram, exploring a specific congressman’s misuse of public funds, color analysis of brand, predicting next season’s runway models.

CALL TO ACTION

This analysis reveals only a sliver of the truth. A more thorough investigation may reveal other biases that we do not immediately think of when interpreting social media studies. I’d love to see a more nuanced dive into Chicago as well as the richer context of our collective social media landscape. (In particular, it would be interesting to see if there are platforms or cities that invert the patterns that are observed in Chicago!)

Expose YOUR city’s social media blindspots!

- Run similar analyses:

- Look at race/ethnicity or other demographics such as socio-economic status, age, and education.

- Look at Instagram and/or other social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Snapchat, Tindr, PokemonGo).

- Look at longer periods of time to filter for tourist / seasonal impacts.

- Post and share your findings!

SPECIAL THANKS:

For making collection of Insta data possible: Instagram API, Charles Proxy, Google GCE, Cron

For allowing for speedy geospatial data mapping: fiona, shapely, RTree (spatial indices!!!)

For guidance into weighting representation: Applied Survey Methods

For demystifying the census: Chicago’s own Joe Germuska for his stackoverflow & Github repo

For inspiration on how to visualize population data: RacialDotMap, RadicalCartography

Note: This post originally appeared on Datascope’s blog here.